Midwest Teaching of Psychology Conferences in the 1990s. The first part of the lesson is his. The second part is my take on teaching attribution.

I will often use this activity at the beginning of the social psychology unit before the students have read about attribution. But over the years, no matter when it occurs, most students still have the reaction Bernstein talks of. Usually, the majority of my students will blame the wife.

Process:

1) I tell the students I have a story to read them and ask them to have a blank sheet of paper and writing implement. They are going to answer a couple questions afterward.

2) I read the story (explaining that a highwayman is an old term for mugger) and end the story abruptly

3) I ask the question, who is responsible--rank the six characters from most to least responsible

3a) NO TALKING YET

4) Because of memory issues, I usually put this on the board:

-wife

-husband

-L1

-L2

-Ferryboat Captain

-Highwayman

5) I then ask who put the FB captain first, then L1, L2 , husband, then wife. This is where lots of hands go up

6) I then ask for who said the highwayman was most responsible--a few hands

7) I then ask those who said the wife was most responsible to explain. Depending upon the class, I will get some really clear responses, but not always. I try to clarify if they are not

8) I then ask those who said that the highwayman was most responsible why the rest of the class was wrong. This really increases emotions on those who feel the need to defend their position and can create a great discussion

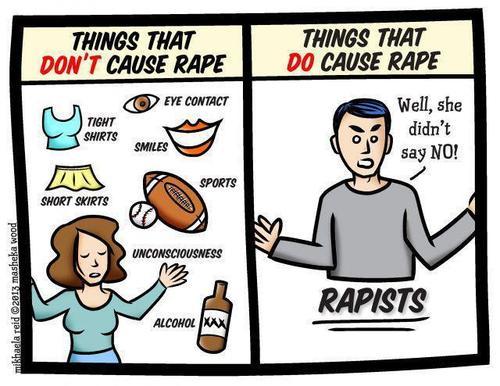

At this point, some or most of the students will get it. I try to add other contexts such as blaming people for being poor or blaming rape victims. I use this second one with great care due to so many having had that experience happen to them. It has sparked some heated discussions in the past.

Attribution of responsibility: Blaming the Victim

Defensive attribution refers to the tendency to blame victims

for their own misfortune (Weiten & Lloyd, 1994). To view victims as somehow

having "asked for it" allows observers to maintain a belief in a "just

world" in which people get what they deserve and deserve what they get (Lerner

& Miller, 1978). Defensive attribution also allows people to sustain the comforting

illusion that they themselves are unlikely to suffer a similar catastrophe.

This exercise was developed by Bloyd (1990) and is based on the

following story, taken from Dolgoff and Feldstein (1984):

Once upon a time, a husband and wife

lived together in a part of the city separated by a river from the places of employment,

shopping, and entertainment. The husband had to work nights. Each evening he left

his wife and took the ferryboat to work, returning in the morning.

The wife soon tired of this arrangement.

Restless and lonely, she would take the next ferry into town each evening and develop

relationships with a series of lovers. Anxious

to preserve her marriage, she always returned home before her husband. In fact,

her relationships were always limited. When they threatened to become too intense,

she would precipitate a quarrel with her current lover and begin a new relationship.

One night she caused such a quarrel

with a man we will call Lover I. He slammed the door in her face, and she started

back to the ferry. Suddenly she realized that she had forgotten to bring the money

for her return fare. She swallowed her pride and returned to Lover 1's apartment

to borrow the fare. After all, she did have to get home. But Lover 1 was vindictive

and angry because of the quarrel. He slammed the door on his former lover, leaving

her with no money. She remembered that a previous lover, who we shall call Lover

2, lived just a few doors away. Surely he would give her the ferryboat fare. However,

Lover 2 was still so hurt from their old quarrel that he, too, refused her the money.

Now the hour was late, and the woman

was getting desperate. She rushed down to the ferryboat and pleaded with the ferryboat

captain. He knew her as a regular customer. She asked if he could let her ride free

and if she could pay the next night. But the captain insisted that rules were rules,

and that he could not let her ride without paying the fare.

Dawn would soon be breaking, and her

husband would be returning from work. The

woman remembered that there was a free bridge about a mile further on. But the road

to the bridge was a dangerous one, known to be frequented by highwaymen. Nonetheless,

she had to get home, so she took the road. On the way, a highwayman stepped of the bushes

and demanded her money. She told him she had none. He seized her. In the ensuing

tussle, the highwayman stabbed the woman, and she died.

Thus ends our story. There have been

six characters: husband, wife, Lover I, Lover II, ferryboat captain, and highwayman.

We would like you to list, in descending order of responsibility for this woman's

death, all the characters. In other words, the one most responsible is listed first;

the next most responsible, second; and so forth.

Typically, about half the students will list the highwayman first

and half will list the wife first (although the other characters in the story are

occasionally assigned primary responsibility for the wife's death). In other words,

students are just as likely to blame the ·victim for her own murder as they are

to blame the perpetrator of the crime. If the wife was stupid enough to walk dangerous

streets alone at night, they say, then perhaps her fate was only what she deserved.

Furthermore, the highwayman was behaving in a manner entirely consistent with his

role as "career criminal"; but the victim, by taking a succession of lovers

and deceiving her husband, clearly overstepped the bounds of her role as wife.

An interesting variation on this exercise is to rewrite the story

such that the victim is a widow who works nights to feed her children, and must

get home in time to relieve the babysitter. In this case, the vast majority of students

will assign primary responsibility for the murder to the highwayman rather than

the victim--despite the fact that the perpetrator's behavior is identical in both

stories.

References

Bloyd , J.R. (1990).

Blaming the victim. Presented at the Seventh Annual Mid-America Conference for Teachers

of Psychology, University of Southern Indiana, Evansville, Indiana.

Dolgoff, R., &

Feldstein, D. (1984). Understanding social welfare (2nd ed.). New York: Longman.

Lerner , M.J., &

Miller, D.T. (1978). The belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion. New York:

Plenum.

Weiten, W ., &

Lloyd , M.A. (1994). Psychology applied to modern life: Adjustment in the'90's (4th

ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Follow-up

Just world hypothesis--ideas that make us feel better about the world to keep us in a relative state of low anxiety and denial. We want to believe that bad things only happen to bad people so we conveniently think that we, ourselves, are good people, so bad things are not likely to happen to us, e.g. I will not get into an accident while driving while impaired or texting; I will not get pregnant or a disease while having sex because that only happens to sluts; etc.

After the long discussion, I present the idea of attribution. I use the chart below to create a basic understanding of internal and external attributions/explanations for their own and other people's behavior.

I then share these examples and examine them as a class:

In addition to internal and external, there is also stable and unstable—for our purposes, we are not concerned with that, though you will encounter it in college.

Examples may include:

If you fail a test, you could say, “I suck at tests” which is internal and stable

OR

You could say, “I had a bad day and was tired” which is internal and temporary/unstable—can lead to a greater effort later

OR

“I failed because I am just not that smart” internal and stable—the person is less likely to study later

Explanations of sports teams we support and why they succeeded or failed (especially good around playoff time for major sports or during March Madness)

Our (white people’s) explanations of why we did not get into college (or get a scholarship)

Our explanations of why people of our own gender or ethnic group are successful (or not)

OR

Parents' explanations of their own child's trouble in class versus the other children

External Attributions

For losing a game:

- they could discuss how the field may have been slippery or the referees were making bad calls.

- One also might talk about the sun being in their eyes

- there was too much noise or too little.

External attributions for winning a game would be

“The team played as one”.

Internal attributions for losing a game might be

“I did not kick the ball hard enough”

“I could have played better defense”

Fundamental Attribution Error (FAE)--I then go over this concept with the class. We tend to underestimate the impact of situational factors when understanding/explaining people's behaviors. Awareness can help us reduce this error.

******If you have additional ideas or alternate ideas on how to teach attribution, please let me know. If you have a lesson to share, let's make you a guest blogger.

posted by Chuck Schallhorn

I use this same exercise as you described, but I immediately follow it with the rewritten story about a widow working nights and have students rank characters as in the first story. Even when putting the stories back-to-back students will rank the "highwayman" more responsible in the second scenario than the first.

ReplyDeleteHi Anonymous. I forgot to mention in the post that I do that as well. Thanks for the reminder.

ReplyDeleteFantastic post! I will be giving this a try!

ReplyDeleteThis is great! I introduced attribution last week and my students are struggling a little, I think this will help...

ReplyDeleteThis is great! I introduced attribution last week and my students are struggling a little, I think this will help...

ReplyDelete